(One of the many wonderful quotes from H L Mencken. See here for more.)

And nowhere is this more true than in health care, where we have so many highly intelligent people, caring deeply about the quality of care patients receive, who can find themselves, in tackling problems, devising solutions that make things worse rather than better.

How can this happen?

One of the reasons is that we can so easily fail to understand the complexity of the environment we are working in, so we fail to identify the underlying trends that are contributing to the problem, and because we do not see them we fail to notice that our response exacerbates them. In other words we tend to look at a snapshot in time and do not explore the historical trends that not only shape our world, but influence how we think and behave.

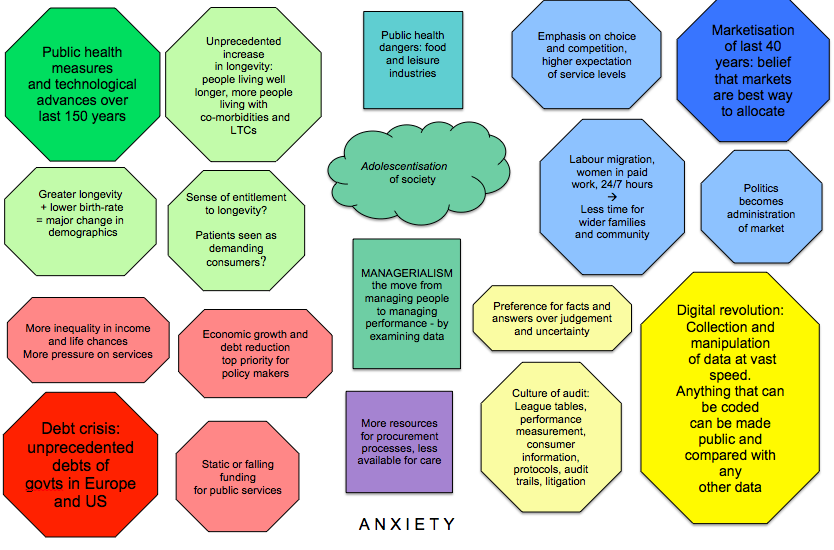

The graphic shown below introduces some of these trends and how they interact with each other to produce a ‘swirl of forces’ around us that, if we remain unaware of it, pushes us to behave in ways that exacerbate problems while thinking we are solving them.

Lets have a look at what trends are represented here.

In each of the four corners there is a different coloured lozenge shape that represents an influence of critical significance.

- Technological advances over the last 150 years.

- The marketisation agenda that has swept democracies around he world over the last 40 years.

- The digital revolution

- The debt crisis in the West.

In the paler lozenges of the same colour some of the consequences of these influences are given.

In the boxes of different shapes in the middle are some significant results of interactions between these ‘corners’, the colours indicating which corners are involved.

Now just imagine that each of these text boxes is a wind. Something that has an influence on us, that we cannot change but must somehow contend with. These winds swirl around us in unpredictable ways, sometimes counteracting each other, sometimes boosting each other’s strength. Sometimes we will experience them as refreshing, energizing, and helpful, and sometimes we will find them gale-force, hindering our progress as we try and steer a path through them. Occasionally they will knock us off our feet or sweep us up and deposit us somewhere different from where we started.

This is the world we face in health care. All of us: patients, professionals, managers, and policy makers. This is what we are finding so exciting and rewarding, and so difficult and frustrating.

When it is the latter we all too easily blame other people or particular events for our difficulties. But this is not the fault of a particular politician or even political party, nor a difficult manager or consultant. It hasn’t arrived because of a particular decision, reform, or crisis.

We are all caught up in this swirl. Them, those people whose actions and answers we blame, and us too. Yes all of us. We all experience these winds and as we do so we respond to them.

Very often we respond in ways that are anxious or fearful. After all, we care about health care and our part in it, so, when we find we cannot offer the kind of service we want to, we are bound to feel anxious. But our anxiety often leads us to take action that exacerbates the problem – energises the swirl, whips up the winds. So, inadvertently, we and our solutions become part of the problem.

We all need to move away from autopilot responses in which our clever brains will swiftly steer us away from anxiety (often before we have even noticed it) by devising for us answers that are clear, simple and wrong.

What do I mean? Here is an example.

Many service providers are fearful that their service will be overwhelmed by demand. That isn’t a surprising fear – we are constantly being told about ‘flatlining’ NHS budgets and steadily increasing demand. As a result many triage systems are put in place. The aim of these systems is seen by the providers as reserving the service for those who really need it. So they are not there to assist the patient trying to access the service but to enable the service to decide whether that patient is worthy of the service. John Seddon and others have demonstrated over and over again how triage of this kind increases demand, not marginally but dramatically, as patients have to persist in seeking care for the needs that have not been met. This additional demand even has a name: failure demand.

I can attest to this personally: recently my daughter had extreme toothache. I’ve never had toothache myself so I can’t empathise fully, but the only other time I’ve seen her this upset was when she had appendicitis. On both occasions her symptoms only became severe enough to warrant attention out of hours. The care we needed for what turned out to be an abscess in a root canal was one 10 minute appointment from a dentist and, 24 hours later when she was bringing up all the contents of her stomach (including the pain killers and antibiotics), a consultation with a GP.

The service given was seven sets of triage (some by 111, some by different out of hours dental and GP services), various appointments around north london, and a 111 decision that she needed an ambulance to take her to A & E, where (no, we went under our own steam) we waited surrounded by posters asking us whether we really needed to be there. NO we didn’t. More than anything we needed a conversation with a person capable of using their professional discretion, rather than an algorithm.

In anxiously trying to protect the time of our most expensive and expert resources we design systems that waste more than they save, costing more for a lesser quality service.

But the pressure on resources is real – we do need to act to ensure they are used wisely and well. But not in ways that make the situation worse. We need to think more widely and care-fully than our automatic (anxious) response of pulling up the drawbridge.

If we can see the underlying trends and their impact we can devise approaches that do not originate in anxiety and blame. Then we design very different solutions.

For example: we stop seeing people seeking care as the enemy, and stop trying to divide them into deserving and undeserving. We stop seeing politicians as conniving and self serving and see them as caught as helplessly as we are. And, when we see that everyone in this swirl is afflicted with the same feelings of anxiety and helplessness that we are experiencing, we can look for ways of working constructively with them.

Instead of seeking people we can blame we instead identify the things that are important to us and to them, the aspects of care we so dearly want to protect or improve. Then we can look for potential allies in our struggle to do so. Very often the people we see as a problem will turn out to be a resource.

This isn’t magic, that swirl of forces is still there, there are still very real dangers that things we value will be lost and we will still have to fight to keep or develop those aspects of care we know are important. But, if we recognise this, the energy we call upon will be very different. We will still be working as hard but our enjoyment of the situation will be greater. Our effectiveness too.

So we need to move away from autopilot where our clever brains will devise those answers that are clear, simple and wrong, and towards as sympathetic and wide ranging an understanding of our context as we can.

You can follow up more info on the swirl and on one particular aspect of care it is in danger of driving out here: What is happening to leadership in health care

Or in more detail here: Why Reforming the NHS Doesn’t Work

Hi Valerie, I enjoyed reading this as much as I have your other posts. The Reith Lectures this year seem to deal with the same subject. I am currently supporting the clinical services review in Dorset, specifically on long-term conditions. Your exploration of the forces we are feeling buffeted by is as insightful as ever! It also reminded me of Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Fast & Thinking Slow’. Are immediate response is type 1 thinking, where we need to give ourself time and space to use type 2 thinking. The problem is that we only have a limited capacity for type 2 thinking.

VBW

Craig